If you’ve ever asked Siri a question, chatted with a customer support bot, or played around with ChatGPT, you’ve already seen natural language processing (NLP) in action. But have you ever wondered: How do these systems actually understand what I’m saying? That question is what first got me curious about NLP, and now, as a high school student diving into computational linguistics, I want to break it down for others who might be wondering too.

What Is NLP?

Natural Language Processing is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI) that helps computers understand, interpret, and generate human language. It allows machines to read text, hear speech, figure out what it means, and respond in a way that (hopefully) makes sense.

NLP is used in tons of everyday tools and apps, like:

- Chatbots and virtual assistants (Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant)

- Translation tools (Google Translate)

- Grammar checkers (like Grammarly)

- Sentiment analysis (used by companies to understand customer reviews)

- Smart email suggestions (like Gmail’s autocomplete)

How Do Chatbots Understand Language?

Here’s a simplified view of what happens when you talk to a chatbot:

1. Text Input

You say something like: “What’s the weather like today?”

If it’s a voice assistant, your speech is first turned into text through speech recognition.

2. Tokenization

The text gets split into chunks called tokens (usually words or phrases). So that sentence becomes:

[“What”, “’s”, “the”, “weather”, “like”, “today”, “?”]

3. Understanding Intent and Context

The chatbot has to figure out what you mean. Is this a question? A request? Does “weather” refer to the forecast or something else?

This part usually involves models trained on huge amounts of text data, which learn patterns of how people use language.

4. Generating a Response

Once the bot understands your intent, it decides how to respond. Maybe it retrieves information from a weather API or generates a sentence like “Today’s forecast is sunny with a high of 75°F.”

All of this happens in just a few seconds.

Some Key Concepts in NLP

If you’re curious to dig deeper into how this all works, here are a few beginner-friendly concepts to explore:

- Syntax and Parsing: Figuring out sentence structure (nouns, verbs, grammar rules)

- Semantics: Understanding meaning and context

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Detecting names, dates, locations in a sentence

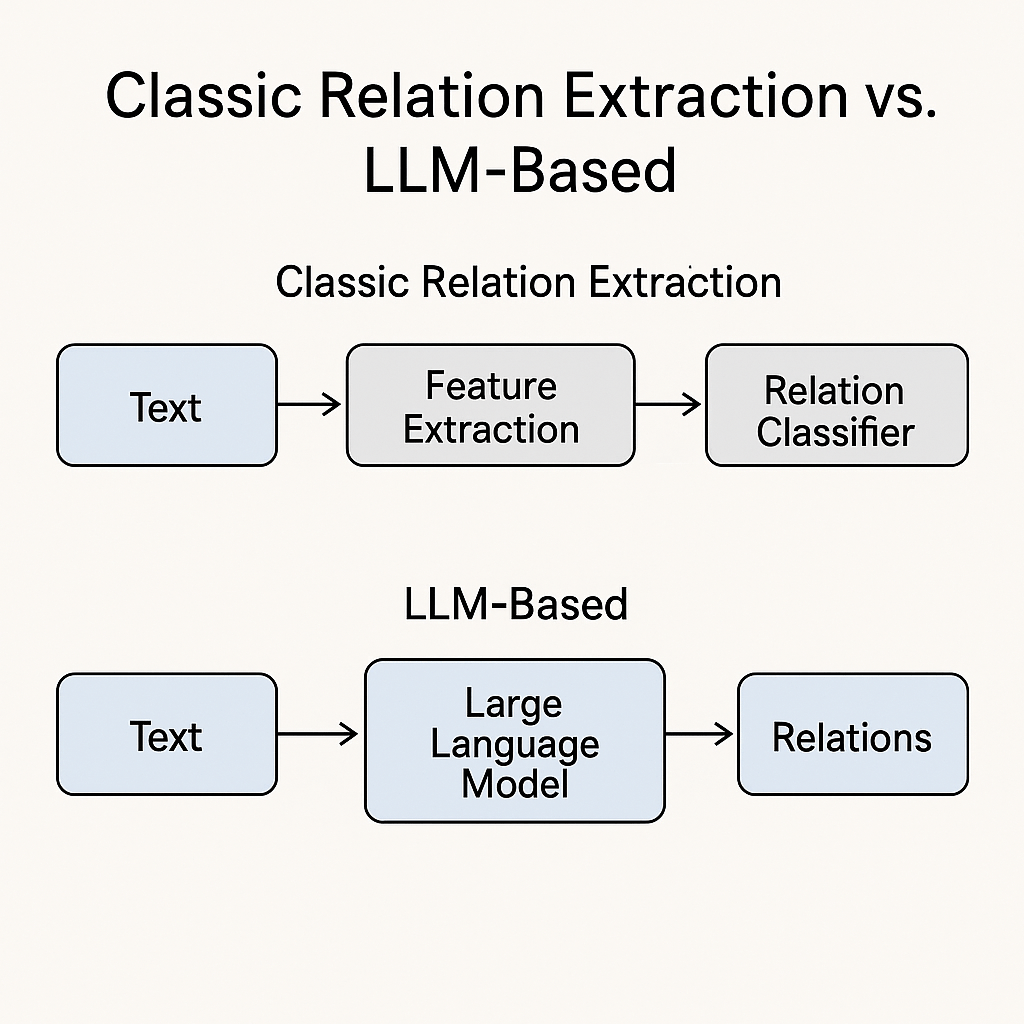

- Language Models: Tools like GPT or BERT that learn how language works from huge datasets

- Word Embeddings: Representing words as vectors so computers can understand similarity (like “king” and “queen” being close together in vector space)

Why This Matters to Me

My interest in NLP and computational linguistics started with my nonprofit work at Student Echo, where we use AI to analyze student survey responses. Since then, I’ve explored research topics like sentiment analysis, LLMs vs. neural networks, and even co-authored a paper accepted at a NAACL 2025 workshop. I also use tools like Zotero to manage my reading and citations, something I wish I had known earlier.

What excites me most is how NLP combines computer science with human language. I’m especially drawn to the possibilities of using NLP to better understand online communication (like on Twitch) or help preserve endangered languages.

Final Thoughts

So the next time you talk to a chatbot, you’ll know there’s a lot going on behind the scenes. NLP is a powerful mix of linguistics and computer science, and it’s also a really fun space to explore as a student.

If you’re curious about getting started, try exploring Python, open-source NLP libraries like spaCy or NLTK, or even just reading research papers. It’s okay to take small steps. I’ve been there too. 🙂

— Andrew

4,811 hits