I’ve always been curious about how language can reveal hidden clues. One place this really shows up is in phishing emails. These are the fake messages that try to trick people into giving away passwords or personal information. They are annoying, but also dangerous, which makes them a great case study for how computational linguistics can be applied in real life.

Why Phishing Emails Matter

Phishing is more than just spam. A single click on the wrong link can cause real damage, from stolen accounts to financial loss. What interests me is that these emails often give themselves away through language. That is where computational linguistics comes in.

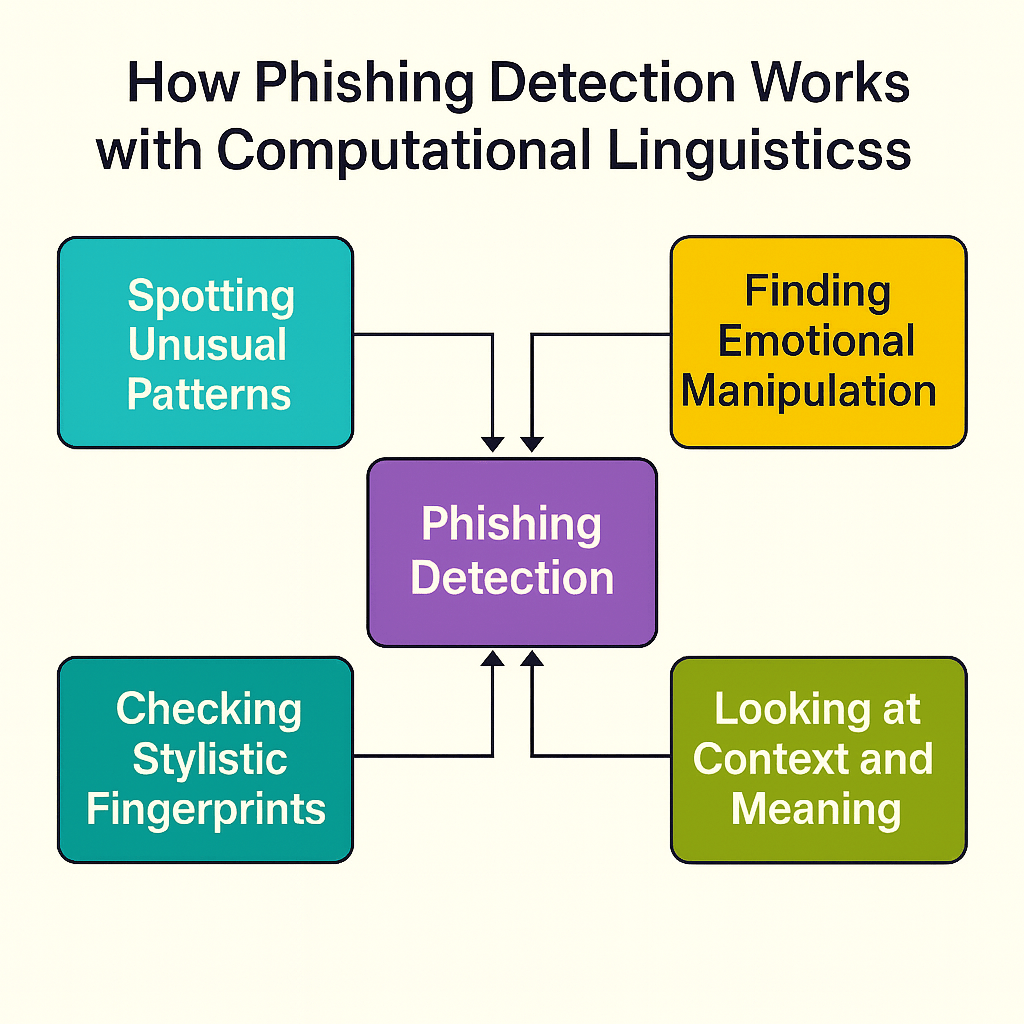

How Language Analysis Helps Detect Phishing

- Spotting unusual patterns: Models can flag odd grammar or overly formal phrases that do not fit normal business communication.

- Checking stylistic fingerprints: Everyone has a writing style. Computational models can learn those styles and catch imposters pretending to be someone else.

- Finding emotional manipulation: Many phishing emails use urgency or fear, like “Act now or your account will be suspended.” Sentiment analysis can identify these tactics.

- Looking at context and meaning: Beyond surface words, models can ask whether the message makes sense in context. A bank asking for login details over email does not line up with how real banks communicate.

Why This Stood Out to Me

What excites me about this problem is that it shows how language technology can protect people. I like studying computational linguistics because it is not just about theory. It has real applications like this that touch everyday life. By teaching computers to recognize how people write, we can stop scams before they reach someone vulnerable.

My Takeaway

Phishing shows how much power is hidden in language, both for good and for harm. To me, that is the motivation for studying computational linguistics: to design tools that understand language well enough to help people. Problems like phishing remind me why the field matters.

📚 Further Reading

Here are some recent peer-reviewed papers if you want to dive deeper into how computational linguistics and machine learning are used to detect phishing:

- Recommended for beginners

Saias, J. (2025). Advances in NLP Techniques for Detection of Message-Based Threats in Digital Platforms: A Systematic Review. Electronics, 14(13), 2551. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14132551

A recent review covering multiple types of digital messaging threats—including phishing—using modern NLP methods. It’s accessible, up to date, and provides a helpful overview. Why I recommend this: As someone still learning computational linguistics, I like starting with survey papers that show many ideas in one place. This one is fresh and covers a lot of ground. - Jaison J. S., Sadiya H., Himashree S., M. Jomi Maria Sijo, & Anitha T. G. (2025). A Survey on Phishing Email Detection Techniques: Using LSTM and Deep Learning. International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET), 13(8). https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2025.73836

Overviews deep learning methods like LSTM, BiLSTM, CNN, and Transformers in phishing detection, with notes on datasets and practical challenges. - Alhuzali, A., Alloqmani, A., Aljabri, M., & Alharbi, F. (2025). In-Depth Analysis of Phishing Email Detection: Evaluating the Performance of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models Across Multiple Datasets. Applied Sciences, 15(6), 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15063396

Compares various machine learning and deep learning detection models across datasets, offering recent performance benchmarks.

— Andrew

4,811 hits