According to ACM TechNews (Wednesday, December 17, 2025), ACM Fellow Rodney Brooks argues that Silicon Valley’s current obsession with humanoid robots is misguided and overhyped. Drawing on decades of experience, he contends that general-purpose, humanlike robots remain far from practical, unsafe to deploy widely, and unlikely to achieve human-level dexterity in the near future. Brooks cautions that investors are confusing impressive demonstrations and AI training techniques with genuine real-world capability. Instead, he argues that meaningful progress will come from specialized, task-focused robots designed to work alongside humans rather than replace them. The original report was published in The New York Times under the title “Rodney Brooks, the Godfather of Modern Robotics, Says the Field Has Lost Its Way.”

I read the New York Times coverage of Rodney Brooks’ argument that Silicon Valley’s current enthusiasm for humanoid robots is likely to end in disappointment. Brooks is widely respected in the robotics community. He co-founded iRobot and has played a major role in shaping modern robotics research. His critique is not anti-technology rhetoric but a perspective grounded in long experience with the practical challenges of engineering physical systems. He makes a similar case in his blog post, “Why Today’s Humanoids Won’t Learn Dexterity”.

Here’s what his core points seem to be:

Why he thinks this boom will fizzle

- The industry is betting huge sums on general-purpose humanoid robots that can do everything humans do—walk, manipulate objects, adapt to new tasks—based on current AI methods. Brooks argues that belief in this near-term is “pure fantasy” because we still lack the basic sensing and physical dexterity that humans take for granted.

- He emphasizes that visual data and generative models aren’t a substitute for true touch sensing and force control. Current training methods can’t teach a robot to use its hands with the precision and adaptation humans have.

- Safety and practicality matter too. Humanoid robots that fall or make a mistake could be dangerous around people, which slows deployment and commercial acceptance.

- He expects a big hype phase followed by a trough of disappointment—a period where money flows out of the industry because the technology hasn’t lived up to its promises.

Where I agree with him

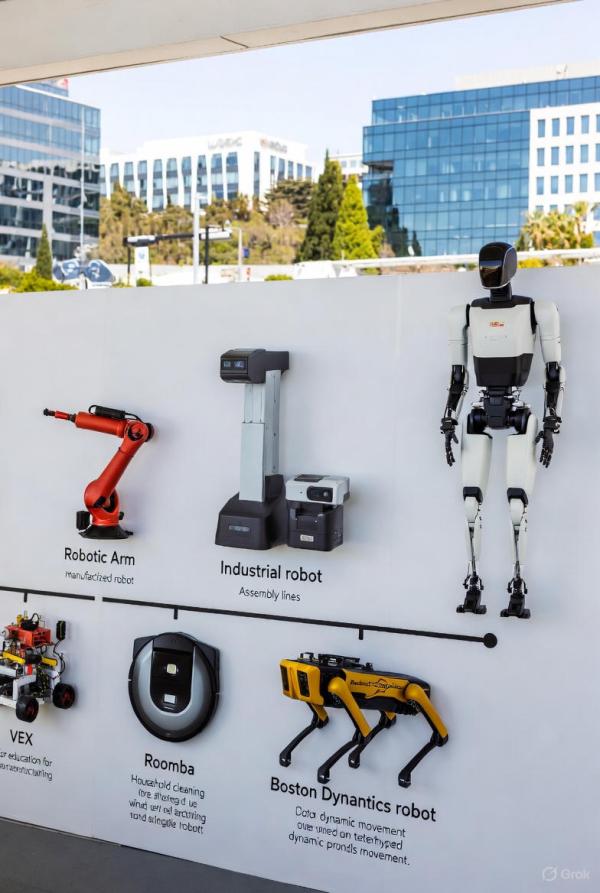

I think Brooks is right that engineering the physical world is harder than it looks. Software breakthroughs like large language models (LLMs) are impressive, but even brilliant language AI doesn’t give a robot the equivalent of muscle, touch, balance, and real-world adaptability. Robots that excel at one narrow task (like warehouse arms or autonomous vacuum cleaners) don’t generalize to ambiguous, unpredictable environments like a home or workplace the way vision-based AI proponents hope. The history of robotics is full of examples where clever demos got headlines long before practical systems were ready.

It would be naive to assume that because AI is making rapid progress in language and perception, physical autonomy will follow instantly with the same methods.

Where I think he might be too pessimistic

Fully dismissing the long-term potential of humanoid robots seems premature. Complex technology transitions often take longer and go in unexpected directions. For example, self-driving cars have taken far longer than early boosters predicted, but we are seeing incremental deployments in constrained zones. Humanoid robots could follow a similar curve: rather than arriving as general-purpose helpers, they may find niches first (healthcare support, logistics, elder care) where the environment and task structure make success easier. Brooks acknowledges that robots will work with humans, but probably not in a human look-alike form in everyday life for decades.

Also, breakthroughs can come from surprising angles. It’s too soon to say that current research paths won’t yield solutions to manipulation, balance, and safety, even if those solutions aren’t obvious yet.

Bottom line

Brooks’ critique is not knee-jerk pessimism. It is a realistic engineering assessment grounded in decades of robotics experience. He is right to question hype and to emphasize that physical intelligence is fundamentally different from digital intelligence.

My experience in VEX Robotics reinforces many of his concerns, even though VEX robots are not humanoid. Building competition robots showed me how fragile physical systems can be. Small changes in friction, battery voltage, alignment, or field conditions routinely caused failures that no amount of clever code could fully anticipate. Success came from tightly scoped designs, extensive iteration, and task-specific mechanisms rather than general intelligence. That contrast makes the current humanoid hype feel misaligned with how robotics actually progresses in practice, where reliability and constraint matter more than appearance or breadth.

Dismissing the possibility of humanoid robots entirely may be too strict, but expecting rapid, general-purpose success is equally misguided. Progress will likely be slower, more specialized, and far less dramatic than Silicon Valley forecasts suggest.

— Andrew

4,811 hits